On Galway Kinnell

ON GALWAY KINNELL by Marjory Wentworth

The poet’s job to figure out the connection between the self and the world, and to get it down in words that have a certain shape, that have a chance of lasting… Morality makes everything worth more to us.—Galway Kinnell

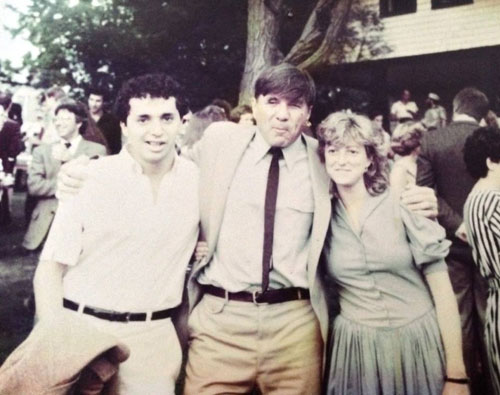

Howard Kaplan, Galway Kinnell, and Marjory Wentworth at Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference c.1984

In the days since Galway Kinnell died, I have received a number of condolence notes and texts from a variety of friends. It’s astonishing how many people dear to me know how important Galway was to me, especially when I was a young poet in New York studying in the NYU creative writing program. He was my teacher and mentor, and he will influence me for the rest of my days. There was nothing ordinary about this great poet. He was such a large presence in all ways. He was built like a football player, and he’s one of those men who quite literally would pick me up when he’d give me a hug if he hadn’t seen me in a long time. His presence always filled a room, but it was his melodic voice and manner that drew people to him. There was a gentleness about him and a kindness that drew you in. In every conversation Galway shared his deep wisdom and his big heart, and I am so lucky to have lived in his bright sphere.

Unlike many graduate students at NYU, I was not a “Galway groupie.” About half of the poetry students had come from far and near to have the chance to study with their favorite poet. Don’t get me wrong, I loved his work but I was also interested in studying with Carolyn Forche, Phil Levine, Louis Simpson and Joseph Brodsky. What I did not realize until I had been in the program for a while, is that Galway was the reason for all these great poets gathered in one place. As Director of the Graduate Creative Writing Program, his choices for faculty had everything to do with his priorities. The program was small and still attached the English Department, and there was an intimacy that felt more like a family than an academic environment.

Galway genuinely loved teaching poetry, and he was devoted to each and every one of us. Our classes were held at night, so that we could work during the day. He felt that this was a realistic and practical consideration. Galway was a kind and supportive workshop leader, and no matter how bad your poem was, he always found something in it that was praiseworthy. I have tried to do the same in workshops that I led. I find myself quoting him quite often when I teach. Galway was challenging as well. Once he made us translate a poem from a language we did not know, because he wanted us to understand that translating poetry was also an art form requiring much more than looking up the meaning of words. I had a hard time with meter, and I still remember sitting in his office while he recited poems (from memory of course) while tapping out the stresses at his desk with a ruler until I could do the same.

He was humble and down to earth and created a supportive environment in which each student found his or her own style and unique expression. Other teachers at NYU, who had experience teaching in similar creative writing programs, described how refreshing it was to teach in a place where all the student poems did not sound the same! There is no doubt that this quality can be attributed to Galway Kinnell. He was extremely generous with his time, and when we went on retreats to student and friend John Chamberlain’s family home in CT once a semester, Galway came too. He cooked dinner, played football, shared poems and walks on the beach. About a year after one of these trips his poem “Chamberlain’s Porch,” was published in New Yorker; we all got a kick out of that.

I was his graduate student assistant: I ran errands for him and typed letters. I answered the telephone in his apartment when he found out he’d won the Pulitzer Prize. That night, he taught the workshop, and we all went out to Eddie’s bar afterwards like we always did. Carolyn Forche brought her workshop, and we were astounded that he wanted to be with his poetry students. He said, “who else would I rather be with?” He always made sure I got to the subway stop, and that night he offered to give me ride to take the F Train back to Brooklyn. His car had been stolen, and he didn’t have insurance. “Let that be a lesson,” he bellowed, “You can win the Pulitzer Prize in poetry but not have enough money for car insurance!” He also shared the National Book Award in poetry that year (1983). I realize only now that the years I was at NYU were the years he received the recognition he deserved.

I stayed in touch with Galway sporadically. One of the last times I saw him was in Washington DC at the Split This Rock, Poets Against The War conference during the Bush years, where he spoke and I was on a couple of panels. We all marched to the White House together and read protest poems one after the other. Galway always had a strong sense of social justice, and had encouraged me when I was working at places like Amnesty International and The Nation Magazine. This kind of support is terribly important when you are young and trying to sort out your subjects and priorities. My first published poem in Beloit Poetry Journal, was a result of his advice, because he suggested I submit there.

If you read his poems closely you witness the humanity that inspired and guided him. There is an attention and sensitivity to things that others might ignore – whether it be the creatures that live among us or strangers on a city street – his poetry celebrates and reminds us of the things we already know are most important in our lives. Poet Liz Rosenberg once wrote: “Kinnell is a poet of the rarest ability, the kind who comes once or twice in a generation, who can flesh out music, raise the spirits and break the heart.” There is no higher praise.

When I read his poems now, I hear his voice in my head. Lucky me. It was a voice like no other – so full of music and emotion. I don’t think that there has ever been a better reader of poetry in the English language, except perhaps Dylan Thomas. I could go on and on, and as I write I think of more stories to share. So I will end with his friend Joseph Brodsky’s favorite saying: …and so on…and so on.

Marjory Wentworth’s poems have appeared in numerous books, magazines, and anthologies. She has been nominated for The Pushcart Prize five times. She is the Poet Laureate of South Carolina. Her first collection of poems, Noticing Eden, was published by Hub City Writing Project in 2003. Her second volume, Despite Gravity, was published by Ninety-Six Press in 2007. Shackles, a children’s book, was published by Legacy Publications in February 2009. Her third collection of poems, The Endless Repetition of an Ordinary Miracle, was released in the spring of 2010 from Press 53. She is the co-writer with Juan Mendez of Taking a Stand, The Evolution of Human Rights published by Palgrave Macmillan in the fall of 2011. New and Selected Poems is just out with the University of South Carolina Press.

.jpg)